My exposure to Go began as a childhood interest. Many Chinese parents encourage their children to learn Go more as a targeted investment rather than simply nurturing an interest. My mother believed that learning Go was beneficial for a child’s intellectual development. Thus, the pursuit of learning Go seemed more about idolizing intelligence rather than seeking enjoyment. I will attempt to discuss Go’s key cognitive abilities from an empirical research perspective in this article.

What is Go?

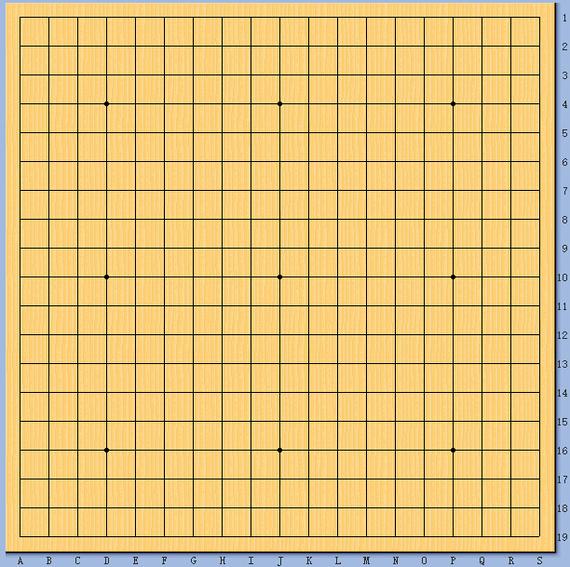

Before delving into a detailed discussion, it’s necessary to define our subject: Go. Go is a board game where two players alternately place stones on a board. Once placed, the stones cannot be moved. When a player’s stones are completely surrounded by the opponent’s, they are removed from the board. The game ends when a certain number of stones are removed, and the player with more stones remaining on the board wins. A standard Go board is a 19x19 grid, and the stones are black and white, placed at the dots (intersections of lines). The Go board looks like the following image:

Basic

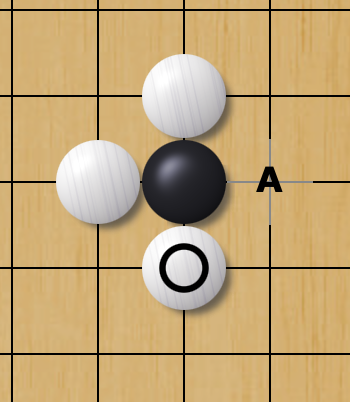

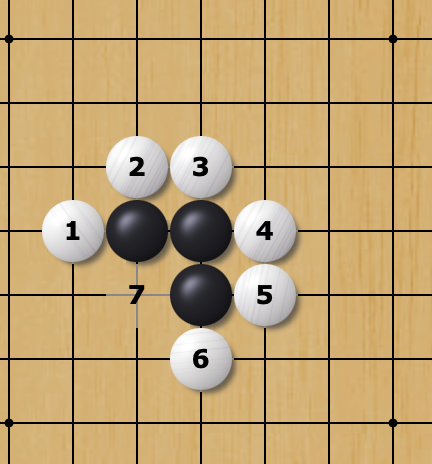

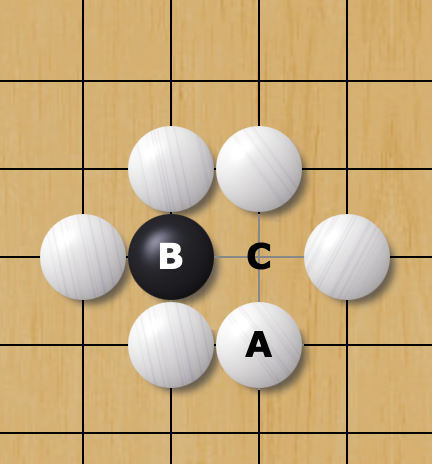

When a stone is surrounded entriely by the opponents, it would be removed from the board.

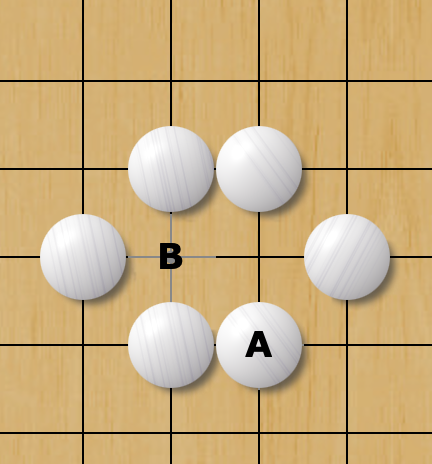

It takes four moves to fully surround a stone. If dot A was possessed by the white stone, the black stone would be removed. The surrounded dot (Dot B) mustn’t be refilled with a new balck stone, known as the “forbidden rule”.

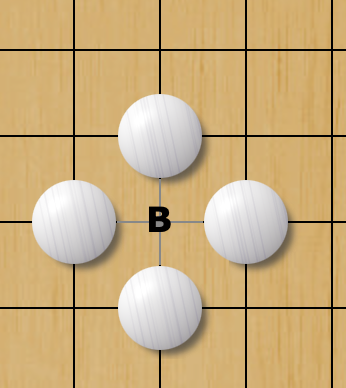

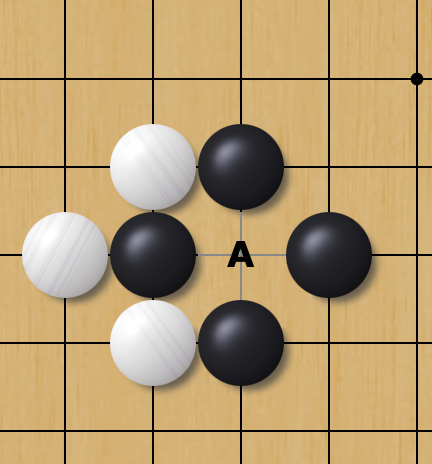

It takes respectively 6, 7steps for white stones to surround black stones in the illustration. Try to make counts of various patterns in a virtual board.

Total Chances

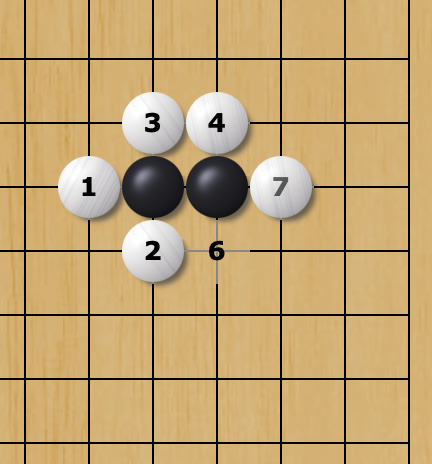

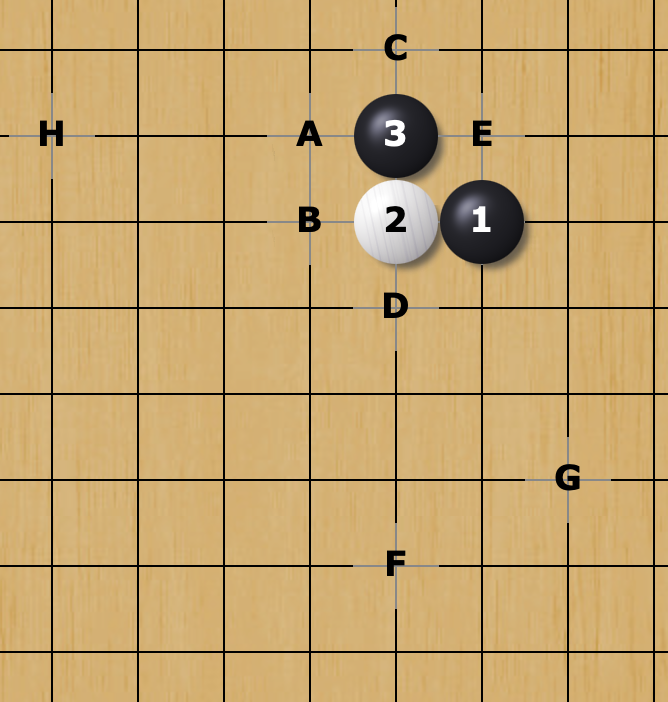

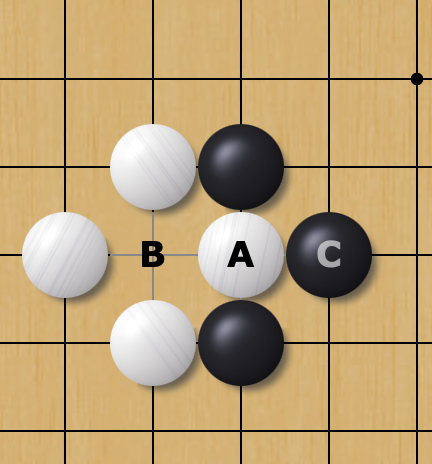

players take turn to make moves.

Three moves have been made by each player. Move 1 and Move 3 by the black, and Move 2 by the white; Move 4 to be determined by white.

The player may choose to make moves on any available dots on the board that has not yet been possessed. This brings tons of available options for each move. Take a 19 X 19 size board as an example, there would be a total of 19 * 19 = 361 available dots on the board. The first move made by balck can be any of these 361 dots. The next step by white would be from the 360 available dots.

The game seemed to be finite with maximum of the following chance for 19 X 19 board:

361 * (361 - 1) * (361 - 2) * … * 1

or

3^361 (About 1.74 * 10^172)

Yet the game get complicated when places with previously removed stones can be refilled with new stones.

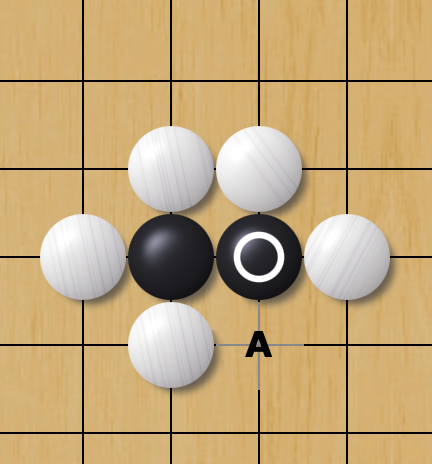

Stones can be placed at dot B, because white must occupy dot 3 for the black stone to be fully surrounded.

Now, what about when stones fully,conjugally surrounded each other?

If a stone is placed at dot A, it can override the “forbidden rule” to settle the removal of the black stone at dot B. Players mustn’t unceasingly make moves in A and B, which makes a loop. Players are allowed to refill A or B 1 turn after a move made at A or B. This brings much more complexity to the game. Several conventional network-like models had been developed to estimate the total chance in the game. Some argued a 363 billion row square matrix for possible states, a number human individuals apparently cannot exhaust.

End Rule

Ending rule of Go is simple: the players with more terriotory wins! Take a 19 X 19 size board as an example, there would be a total of 19 * 19 = 361 available dots on the board. Player with more than half territory about 180.5 dots would be considered as the winner. However, considering players with black stone (pre-determined rule) usually take advantage in ability to priorities strategies at early stages of game, black stone players must compensate the opponent with 6 - 8 dots depending on the specific rules.

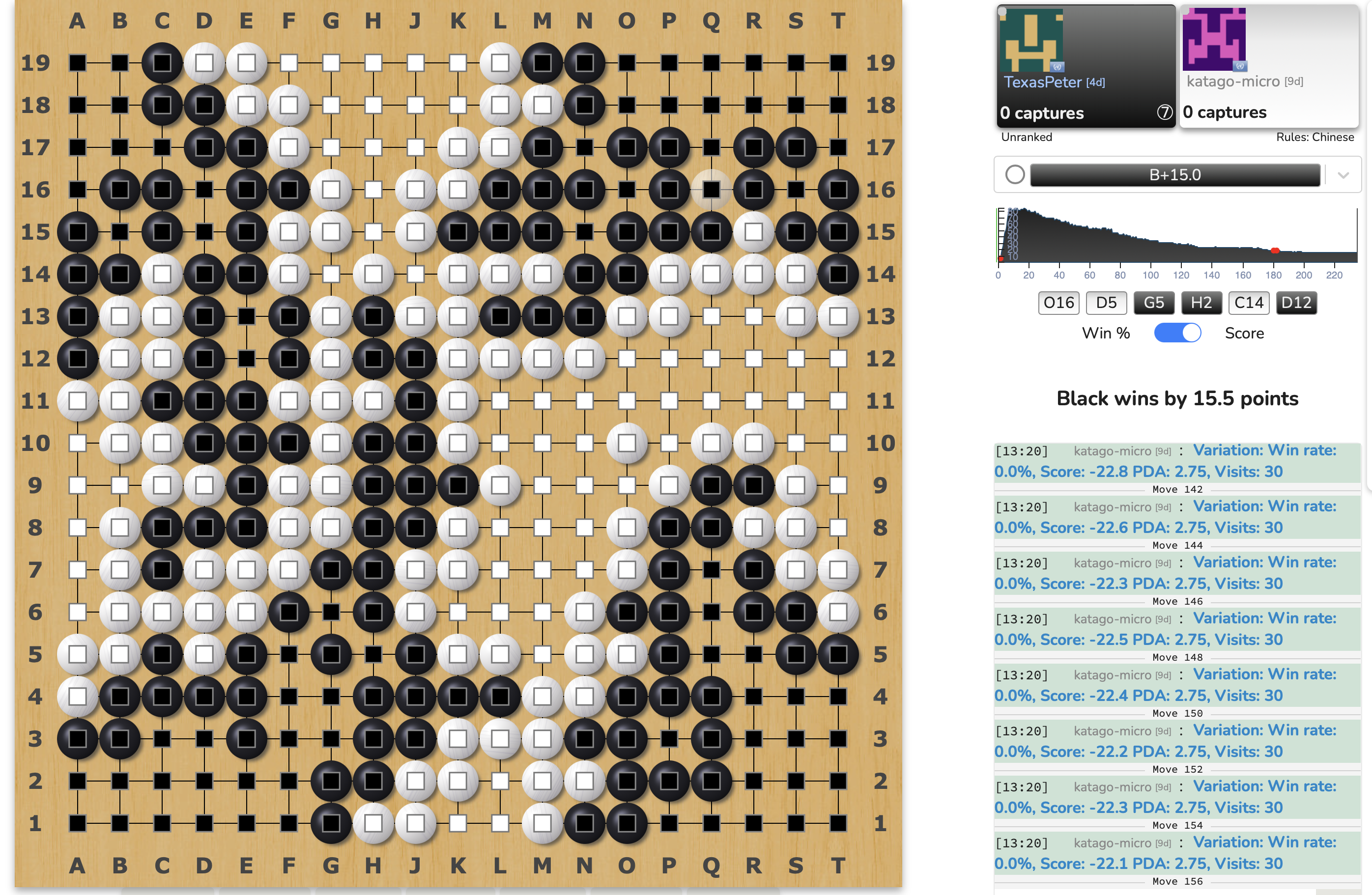

Screenshot of a random Go game on OGS. The game comes the end with 235 total moves. Black wins with more territory. It often takes more than 100 moves to end a game, each of which move can lead the game into a unique direction.

Of course, there are many variations to Go’s rules. For example, the board size can be 9x9. In certain contexts, minor rules of the game might also vary. A well-known example is the endgame rule in Go. In Japan and Korea, the endgame involves “counting points,” while in Chinese rules, it’s about “counting stones” (essentially, both are methods of quantifying territory, but implemented differently). These minor rules don’t touch upon the essence of Go.

TBD